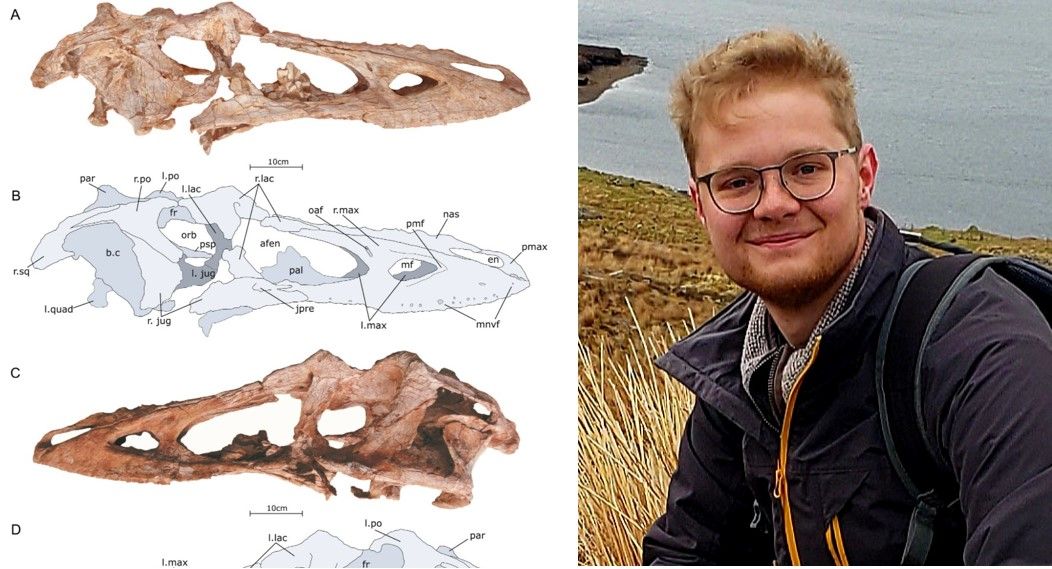

William Foster from Bever lab has published his first paper! Based on part of his master’s thesis, Foster et al describe the cranial anatomy of the Chinese tyrannosaurid dinosaur Qianzhousaurus sinensis.

Check out the full article here:

Abstract

“Tyrannosaurid theropods topped the terrestrial food chain in North America and Asia during the latest Cretaceous. Most tyrannosaurids, exemplified by Tyrannosaurus rex, had deep snouts, thick teeth, and large jaw muscles that could generate high bite forces. They coexisted in Asia with a morphologically divergent group of long-snouted relatives, called alioramins. Qianzhousaurus sinensis, from the Maastrichtian of Ganzhou, China, is the largest alioramin yet discovered, but has only been briefly described. Here we present a detailed osteological description of the holotype cranium and mandible of Qianzhousaurus. We identify several new autapomorphic features of the genus, and new synapomorphies that unite alioramins (Qianzhousaurus, Alioramus altai, Alioramus remotus) as a clade, including a laterally projecting rugosity on the jugal. We clarify that the elongate skull of alioramins involves lengthening of the anterior palate but not the premaxilla, and is reflected by lengthening of the posterior bones of the lower jaw, even though the posterior cranium (orbit and lateral temporal fenestra) are proportionally similar to deep-skulled tyrannosaurids. We show that much of the variation among the alioramin species is consistent with growth trends in other tyrannosaurids, and that A. altai, A. remotus, and Qianzhousaurus represent different ontogenetic stages of progressive maturity, across which the signature nasal rugosites of alioramins became less prominent. We predict that the holotype skull of Qianzhousaurus represents the adult level of maturity for alioramins, and propose that the skull morphology of Qianzhousaurus indicates a much weaker bite than deep-skulled tyrannosaurids, suggestive of differences in prey choice and feeding style.”